One thing's for sure - nothing could silence the prophet's fire. Nothing could hush his righteous indignation. Until now.

William Sloane Coffin is dead, and the Church has lost the voice of prophet at a time when a prophet's voice is so sorely needed.

It's beyond imagination that I was able to call William Sloane Coffin "Bill," only because that's what he wanted me to call him. I have a note he wrote me not long after he preached at Saint John's offering encouragement and appreciation. It is a cherished possession. In my one weekend with him he treated me as an equal. And even as my partner in ministry, truly a friend of Bill's, would visit him, he'd ask about me and about our ministry at Saint John's.

Bill preached in the Saint John's pulpit in February, 2003. Check your history, folks, that's a month before our nation invaded a country that posed no imminent threat to our own. The reasons he shared then about why it was a bad idea, and the church's complacency in a moment such as this are scary when you think about how right he was.

Some saw Bill as anti-American - a sentiment he rejected with every fiber of his being. He loved his country. Loved it enough to have what he'd call a "lover's spat" with it, with hope that she could one day truly live up to her ideal.

Bill Coffin's prophetic witness is needed now more than ever, and those of us who have been touched by his vision must now carry on. Perhaps his last, best lessons he teaches us are those he provides in this Holy Week, that, his "great gettin' up mornin'" has come, and that which he came to know as true in his rhetoric is now true in his dying--for in it is the nature of God.

"Amo, ergo sum."

"I love, therefore, I am."

Rest in Peace, Bill.

What follows appears on the Yale Divinity School website. I've also copied in an article that ran on Bill from an appearance he made a couple of years ago where he reflects upon his failing health and the approach of his death.

William Sloane Coffin Jr., Yale chaplain during the turbulent 1960s, dies

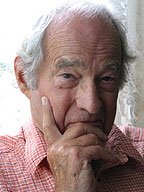

William Sloane Coffin Jr., the fiery Yale University chaplain who inspired a generation of 1960s and 1970s college students with preaching that rankled the establishment even as it engaged the anti-war community, died Wednesday, April 12. He was 81 years old and had been ill for several years. According to family members, the cause of death was a heart attack, suffered while sitting in a rocking chair at his home in Strafford, VT.

Coffin was chaplain at Yale from 1958 until 1975 and then served for a decade as senior minister at Riverside Church in New York City from 1977-87, after which he became president of SANE/FREEZE, later known as Peace Action. In recent years Coffin has spent much of his time writing, including his 2004 national bestseller, Credo, A Passion for the Possible: A Message to U.S. Churches, and Letters to a Young Doubter.

Coffin, who earned an undergraduate degree from Yale in 1949 and a B.D. from Yale Divinity School in 1956, had little patience for any religious style that would draw strict separations between politics and religion. When he perceived injustices, he was prone to come out swinging, even at the risk of offending, leading many to describe his preaching style as “prophetic.”

He was among the “Freedom Riders” who rode the interstate buses in the South in the early 1960s to challenge segregation, and during the Vietnam years he was heavily engaged in protests against the war. He helped organize mobilizations, supported conscientious objectors and acts of civil disobedience.

At an October 1967 protest in Boston over 1,000 draft resisters turned in their draft cards as a church service led by Coffin, leading to his indictment and conviction on charges of conspiracy to aid draft resisters – a conviction that was ultimately overturned. And all of this by a man who once trained to be a concert pianist and who had worked for the Central Intelligence Agency for three years.

During one of his last major public appearances—at a celebration of his life and work held at Yale in April 2005 attended by the likes of Yale football great Calvin Hill, Doonesbury cartoonist Garry Trudeau, and musicians Peter and Paul of Peter, Paul and Mary—Coffin was still prodding and pushing, encouraging seminaries to equip future church leaders to challenge the status quo.

Before an audience of about 400 at the Yale Commons, Coffin summoned the energy to rise from his wheelchair and speak for over 20 minutes. He declared, “Clearly, parish clergy could use a little more starch; they are gumption-deficient. But they also need more instruction from their seminaries to face difficult situations that lie ahead.”

Among those difficult tasks, according to Coffin: the treatment of same-sex couples, pollution, and nuclear proliferation. On issues such as those, he warned, the mainline church community should be prepared to “take on” the religious right.

Despite his public image as a firebrand, though, those who were closest to Coffin knew him as a man who had a gentle, caring interior, a “pastoral” side to his ministry that balanced the prophetic.

The Rev. Ronald Evans, who lived with the Coffin family as a seminarian, recalled, “Though Bill's personality easily filled great spaces and important places, yet he had that rare quality of being every bit as good at the up close and personal as he was in his more widely known pulpit and platform presence... He was the kind of preacher who made every sermon not only a call to action, but was heard as a personal pastoral call.”

Like many other Coffin admirers, Evans well remembers the literary bent that separated Coffin from other preachers who may have said the same things but with not nearly as much style. In particular, Evans recalls some “well-crafted turns of phrase” such as “a world not just for some of us, but truly just for all of us," or "God loves us not becausewe have worth, rather we have worth because God loves us already - AND so readily," or "I have always thought the term 'controversial Christian' a redundancy," Joseph C. Hough Jr., president of Union Theological Seminary in New York, called Coffin “one of God's chosen prophets” in March.

“He is a great patriot who loves his country too much to leave it alone,” said Hough, a 1959 graduate of Yale Divinity School. “ His early and strong leadership in the struggle against segregation and discrimination on the basis of race; his pivotal role in organizing opposition against the war in Vietnam; and his continuing personal investment and national leadership in the campaign to abolish nuclear weapons from an increasingly dangerous world, place him among the most important Christian leaders in American history.

The Rev. Bliss Browne, who earned an undergraduate degree from Yale in 1971 and served as a deacon under Coffin in Battell Chapel, said Coffin had taught her about a “love of justice, love of life” and about “living passionately from the inside out.”

Coffin's legacy of “prophetic imagination,” Browne said, concerns both grief and hope: “We must be willing to name what diminishes and destroys life and willing to name in bold terms the invitation into greater life, to renounce cynicism and choose hope over despair. And we can live in joy, in a way that shows that hope is appropriate and attractive.”

Out of the Yale celebration last year emerged two developments that are likely to extend the Coffin legacy: establishment of the National Religious Partnership on the Nuclear Weapons Danger, and creation of the William Sloane Coffin Jr. Scholarship fund at Yale Divinity School.

The stated purpose of the Partnership is “to work toward the permanent elimination of nuclear weapons by empowering religious communities to take action on a local level.”

“Prophetic leadership,” “passion for justice” and “critical theological interpretations of the contemporary social and political scene,” reflecting the Coffin style, are characteristics that will be sought in Yale Divinity School students who are named Coffin Scholars. The fund has an endowment goal of $1 million—about $500,000 has been raised to date—and was initiated by former students who were deeply influenced by Coffin's ministry.

Plans are under way for a memorial service in Coffin's honor to be held in June during reunion week. As plans are finalized, updates will be posted on the Yale Divinity School web site.

Coffin and his life's work will no doubt be remembered, and have an impact, for many years to come. Over the course of the last half-century his name has become a yardstick of sorts in the broader world of faith and life. Ironically, perhaps providentially, in an issue that hit the newsstands just this week, The Nation magazine hailed Coffin's continuing engagement: “When asked who is the contemporary equivalent of Coffin...several mainline Christians signed and said, ‘Well, I guess—Coffin.”

Social-justice firebrand Coffin is anticipating a gentle, quiet death

[4-7-04]by Alexa Smith, Presbyterian News Service

LOUISVILLE - April 7, 2004 - Having spent his life raging against bigotry, nuclear arms and economic excess, the Rev. William Sloane Coffin says he intends to die gently, without fuss, without fury.

"We should cooperate gracefully with the inevitable," he says pragmatically, acknowledging with some amusement that, while he's had a fiery public life, he is a man who picks his battles. "If you don't come to grips with death early on, but know you'll die, it will make you insecure. And that's the worst thing that humans can do, try to secure themselves against insecurity. With money. Or power. Pretending that life will go on forever. And it makes others pay a gruesome price.

"You see, you can't get rich without making someone else poor. You can't get power without disempowering somebody else. All of these things are forms of pride ... and are essentially corrupt."

At 79, Coffin's words still flow flawlessly. He is ever the preacher.

Coffin, who has been the voice of northern liberal religious dissent for a quarter-century, is a magnet for controversy. Ironically, he was an Army and CIA veteran in 1969 when he became a defendant in the "Boston 5" draft-resistance trial. He achieved fame while serving as chaplain at his alma mater, Yale University, as a lightning rod for opposition to the Vietnam War. A man born to privilege, he was jailed many times as a civil rights Freedom Rider, the first time in 1961. He was senior minister of Riverside Church in Manhattan for more than 10 years, and is president emeritus of SANE/FREEZE: Campaign for Global Security.

Since he suffered a stroke, Coffin's speech is slightly slurred; he sometimes must repeat a word or two. His voice doesn't boom like it used to, but he can still rant against what he finds intolerable - lately the duo of Bush and Cheney, men he believes are muddied by deception and are putting U.S. soldiers' lives at risk in a war with Iraq that shouldn't even be.

This morning, however, at his daughter's home in Oakland, CA, he is talking about death, and not just philosophically. He may not see another Easter this side of eternity. But he acknowledges death casually, like a man awaiting the first snowflake of the winter, not knowing its day or time.

He complains that he's short of breath before he even gets out of bed, and says his tennis-player legs are "pretty well gone." He can walk around the house, but needs a wheelchair to leave it, and usually needs his wife, Randy, the woman who helped him learn to speak again after his stroke, to push it. And there are grandkids always happy to push Poppy around. Without slapping a technical diagnosis on his condition, Coffin says that his heart is "thickening," which means that less and less blood gets pumped through it.

"I can do some things. I write a bit. ... I have not lost my marbles," he says, describing his good fortune to have a new book published by Westminster/John Knox Press, Credo, a compilation of quotes that is rapidly climbing the best-seller lists and on which he, happily, did little of the work. [Click here for Gene TeSelle's review of Credo, and a link to order the book.]

His old friend Bill Moyers recently interviewed him on NOW, about his life, about his impending death. There's a documentary, "Coffin's Lover's Quarrel with America." Warren Goldstein has just published a biography, William Sloane Coffin Jr.: A Holy Impatience, published, appropriately, by Yale University Press. [Click here for a note about Goldstein's book.]

"I've got nothing to complain about," he says.

While Credo is rife with rage about a lack of justice in the world, the callousness of the rich, and Christians' reluctance to confront both, it is evident from its opening, Faith, Hope and Love, through the final chapter, The End of Life, that God is the central character in this volume - and Coffin's strength and comfort.

At its close, he contradicts the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, saying: "The only way to have a good death is to lead a good life. Lead a good one, full of curiosity, generosity, and compassion, and there's no need at the close of the day to rage against the dying of the light. We can go gentle into that good night."

There is no rage here, even though that may seem ironic to some.

Early on, Coffin got his mind around the core of a faith that has irony at its heart: Where love is the mightiest power, where unmerited good is as much a marvel as evil, and where a life put in God's good hands can instill hope and life even in the face of death.

It was out of such conviction that Coffin to delivered a now famous eulogy for his son, Alex, absolving God of any blame in his death in a car accident and rejecting the platitude that human suffering is part of God's will. "Nothing infuriates me as much as the incapacity of seemingly intelligent people to get it through their heads that God doesn't go around this world with his fingers on triggers, his fists around knives, his hands on steering wheels," he says. "... The one thing that should never be said when someone dies is, 'It is the will of God.' Never do we know enough to say that. My own consolation lies in knowing that it was not the will of God that Alex die; that when the waves closed over the sinking car, God's heart was the first of all our hearts to break."

So the man whose social conscience is easily offended by human callousness - especially in people in power - doesn't feel one ounce of anger toward God. "I just don't," he says flatly. "If I am lucky enough to see God one day, I'll have a few questions. But God will have many more to ask me, if he's keeping tabs."

He quotes Paul as his expert, reciting the verse, "Whether we live or die, we are the Lords's."

"Paul says: From God, to God, in God again," he says, adding: "People ask me whether I think I'll see my son again. ... But I do not ... know. I need to know I'll be in God's hands. To demand anything more belittles your faith."

Unmerited cruelty baffles Coffin, but he's more fascinated by the opposite question: How to explain unmerited good?

"You have to be very tough-minded about God," he says. "If love is the name of the game, then freedom is the only pre-condition. Love is self-restricting when it comes to power. The only way God can stop the barbarous things that happen on earth is to restrict our freedom." Something God won't do.

"We have to accept responsibility that the name of the game is love."

That's what teased him into faith in the first place - over time. "I've never had anything as dramatic as the Damascus Road," he says. "I've had mini-conversions, moments when I could see things more clearly."

As a not-particularly-religious college student, Coffin found himself listening to an Episcopal priest intone the liturgy for two friends who'd been killed in a car accident. While the clergyman's voice sounded nasal and smug (Coffin thought about tripping the man as he walked down the aisle), the words threw him slightly off-balance: "The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away." It was the "giveth" part that put his mind into motion, a corrective to his youthful pride. "I just thought, 'You know, Coffin, you're only a guest here. ... A guest, at best.'"

He realized, as he sang in the Yale choir, "All of our hearts are open, all of our desires known," that unless the heart is full of love, the mind can't think straight.

And it was on a whim that he signed up to go to Union Theological Seminary one Monday for a "call to ministry" visit, during which he was bowled over by the visions of justice held out by Reinhold Neibuhr and others. "It was all gradual," he says now.

His theology and his politics combined to push him to the forefront of the social movements that defined his times.

Death may be inevitable, he says, but atrocities and injustices are not.

Mention the war in Iraq, and he says that he wishes the military brass had quit in protest. "Bush, Cheney, Pearl ... (they're) intellectually in a bunker. They're lacking in imagination, and have misled the country, including the military. I feel sympathy for those who are in Iraq."

Coffin says the churches have grown too conservative, like the whole country, forgetting that the devil tempted Jesus with wealth and power. He thinks his thesis in a book published in the 1980s by Westminster/John Knox, A Passion for the Possible, still holds up - that the world the churches ought to be working to create is one without violent conflict, without pollution, and without "a yawning chasm" between rich and poor.

Some churches are "irrelevant(ly) righteous," he says, and others are "more concerned with free love than free hate." He says the answer to bad religion isn't no religion - it's good religion. He laments that much about church life is "management and therapy. There is so little prophetic fire."

"Anger has a very important spiritual benefit," Coffin says. "If you don't have anger, you end up tolerating the intolerable - and that's intolerable. I still have plenty of anger that is ready to be used at a moment's notice."

He pauses, then adds: "When you get older, you find that you don't miss as much as you thought you would. I was a damn good tennis player. Now, I can hardly walk ... I don't grieve that. I was a serious pianist. But I no longer have the energy to keep up my digital dexterity. So, I listen to music; I don't play it. If you adapt in this way, it is a positive thing. You're not in control anymore, less and less. And that's very nice. ...

"As I think I have said other places, it's a very good thing we don't live forever. ... If life were endless, we'd be bored to death. ... The fact that we're going to die gives meaning to life, gives meaning to our days. And that is a good thing."

No comments:

Post a Comment